Listen beyond the birds.

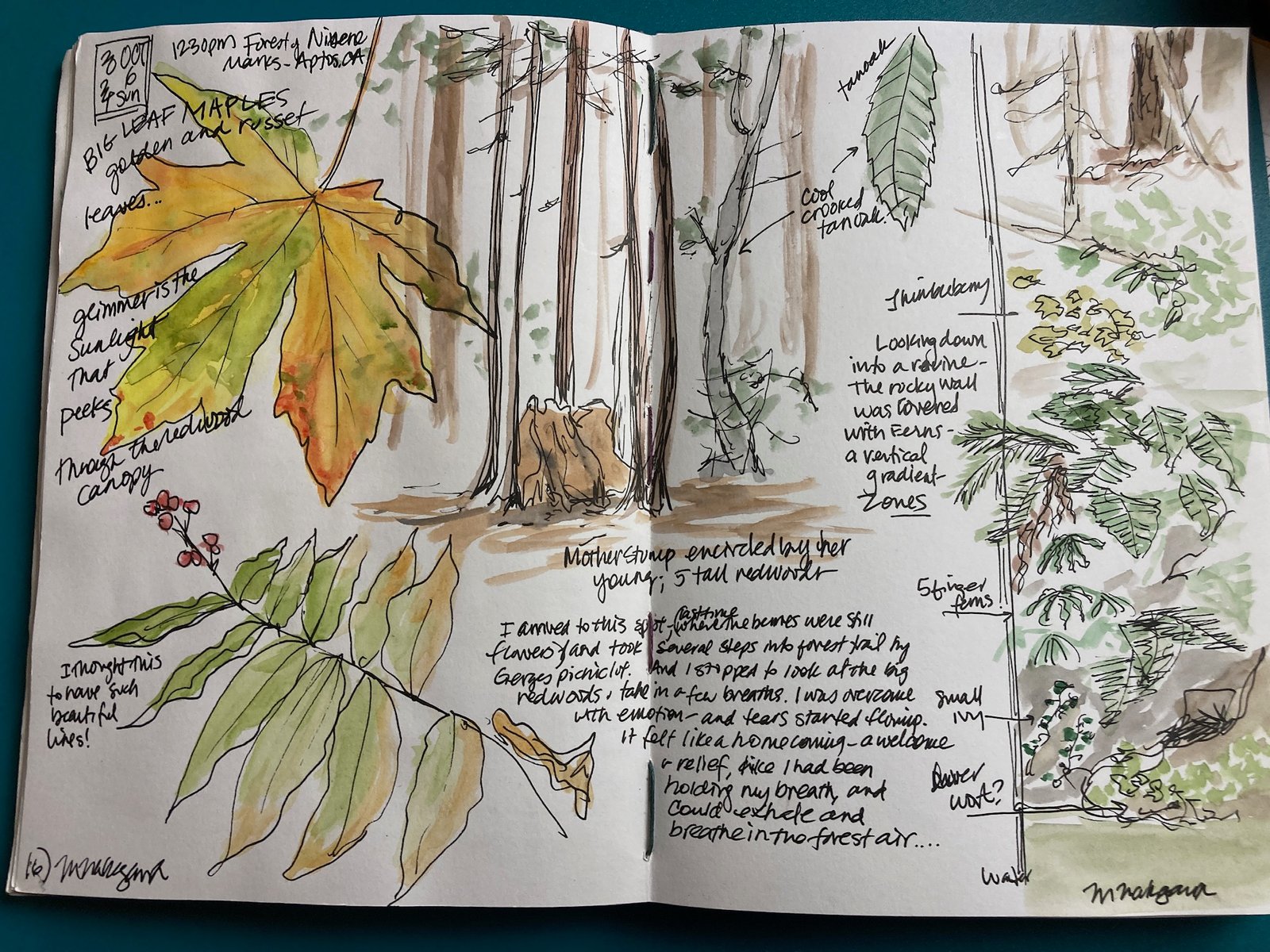

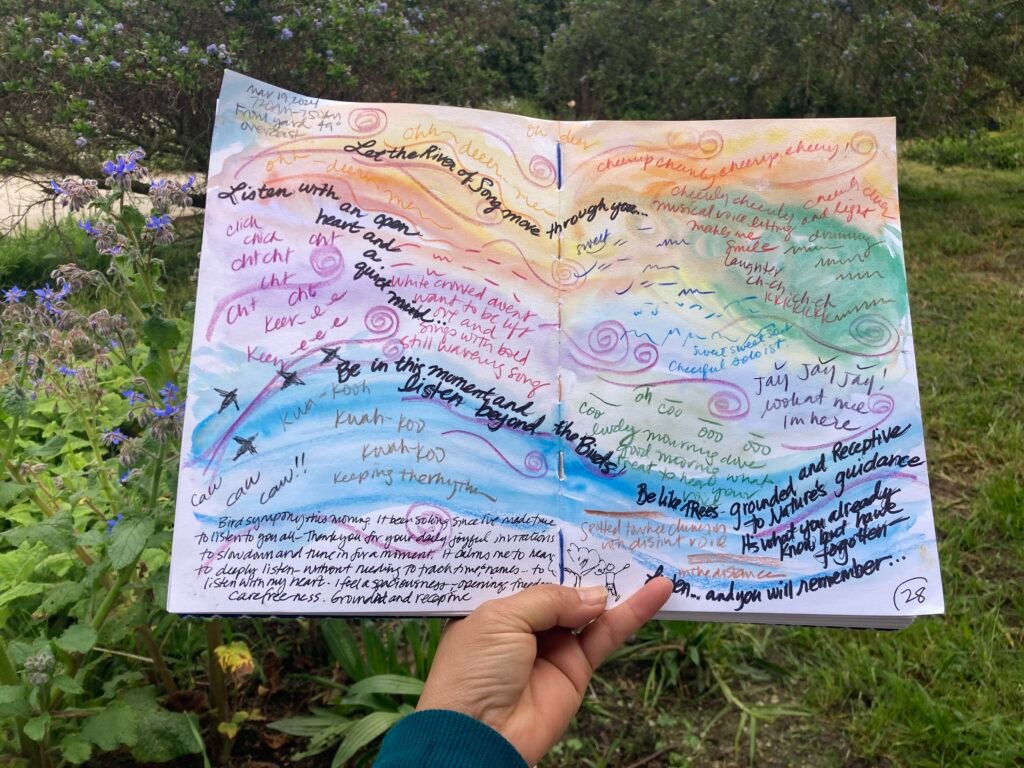

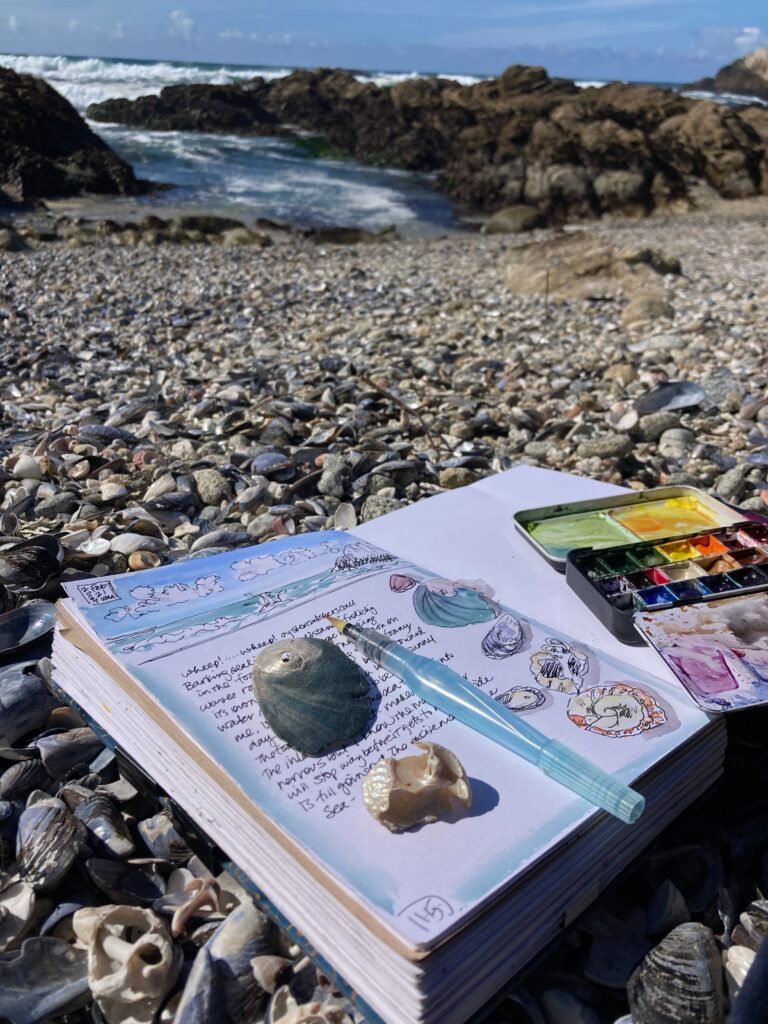

“My nature journal is scratch paper for my conversations with nature,” Melinda Nakagawa told me, as if this were the most ordinary thing in the world. Not a leather-bound keepsake, not a portfolio of botanical prints—scratch paper. It’s the page you do the math on before you write the answer, the place where the crossed-out lines and the wrong turns are allowed to remain. In Nakagawa’s telling, that is the point. Conversation is rarely linear, and the nonhuman world—birds, roses, a green frog that recently occupied her chair—tends to answer in oblique ways.

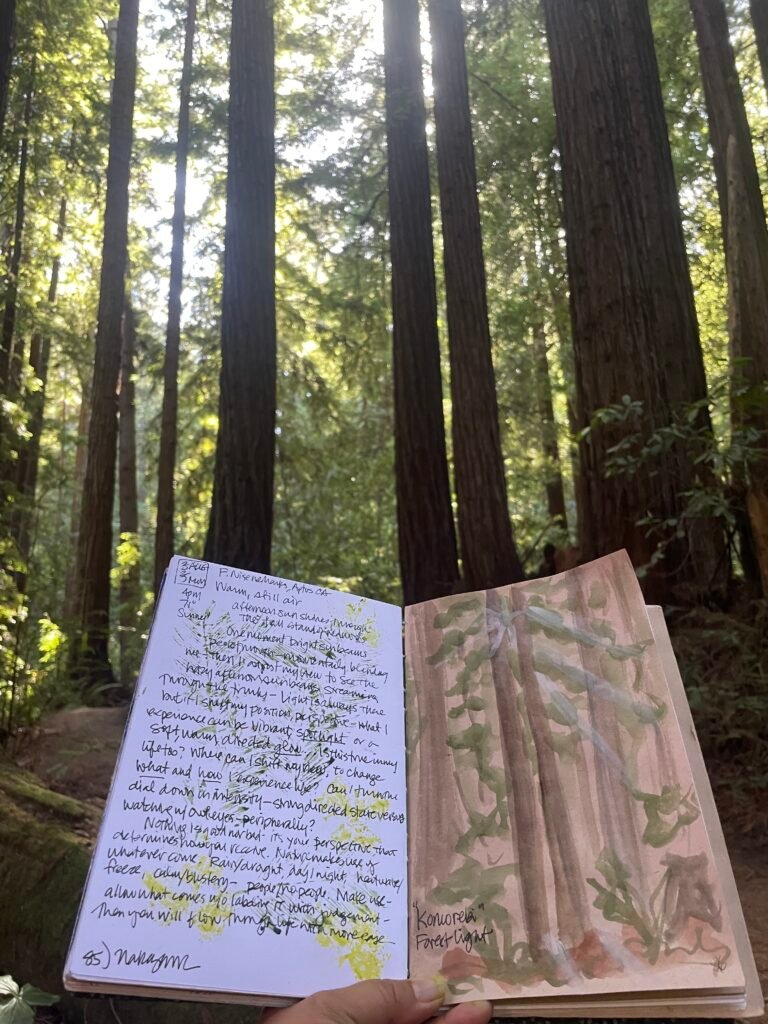

Nakagawa, a scientist by training and a naturalist by profession, did not set out to found a school of anything. The practice began, more than twenty-five years ago, with a split. She kept a diary for the inner weather—gratitude, confusion, all the ordinary emotional musings—and, separately, a notebook to identify different bird species. “I’d write where I saw them and what I thought they were,” she said. The bird notes felt wrong in the diary; the diary felt too confessional for field data. She reached for an old sketchbook. Without naming it, she had made room for a third thing: a place to notice. If you’re looking for a branded method, she is politely disloyal to the genre. “It’s like yoga,” she said. The poses are there, yes, but each teacher carries her own body, her own history, into the room. Two people can observe the same poppy and return with different pages.

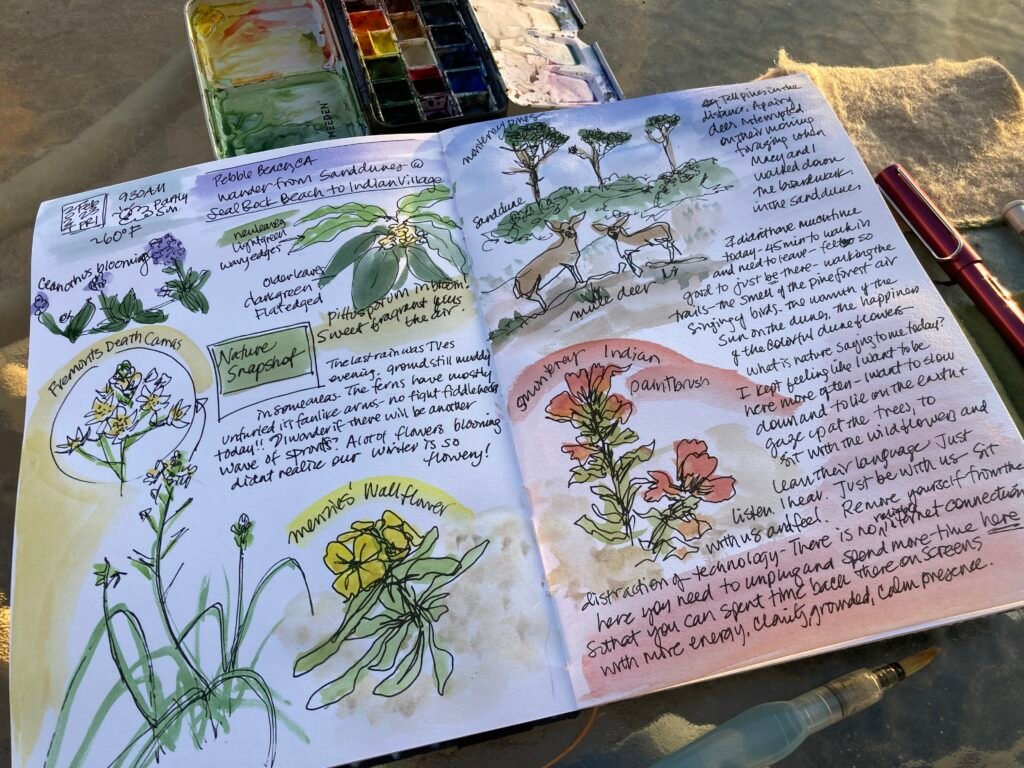

Nakagawa’s pages are often loose to the point of mutiny—continuous contour lines that wobble, scribbles that approximate birdsong, fast notes written before the thought is fully formed. The goal is not a gallery wall. The goal is attention that can bear imperfection.

Before 2020, her entries were often the kind that soothe a scientist’s heart: measurements, species identifications, the clean certainties of a field notebook. A daily habit changed the chemistry. “What kept bubbling up,” she said, “was the phrase listen beyond the birds.” The line sounds grand until you see what it does on paper. The drawings loosen. Colors arrive to stand in for sound. She starts to track how a place feels before she knows why. No one, least of all Nakagawa, would claim peer review for any of this. But the project, she insists, is not anti-scientific; it’s simply wider.

Her metaphor for that widening is watercolor on wet paper—one color dropped into a damp field, then another, their edges finding each other in a soft blur, the new hue neither quite red nor quite blue. For years, she kept her spiritual life and her scientific work on separate sheets. Teaching knocked down the partition. “When those parts finally met,” she said, “I could be myself.” The resulting purple, she argues, is less mystical conflation than relief: the right to bring full attention, with all its ways of knowing, to the same leaf.

What follows from that stance is unglamorous and oddly disarming. If you are nature—as in, made of the same atoms as the poppy and the rock and the deer, exchanging gases with a coast live oak—then the line between “me” and “everything else” is more negotiable than we’re taught. The lettuce in your refrigerator is not scenery; it is relation— a part of nature, like you. One can see how this might sound like sentiment. Nakagawa’s defense is austere: “We’re energetic beings; our hearts run on electricity.” She seems apprehensive of language that keeps people at arm’s length from the obvious.

Her stories are the opposite of arm’s length. One morning, on her way to a backyard sit-spot, she found a frog seated primly on her chair. She relocated it to a potted plant, where it held her gaze, unblinking, for ten minutes—a long time, if you’re counting. The sentence that arrived—“Be still until it’s time”—reads like a fortune cookie on the page, and yet there is the stubborn fact of the frog, and of a woman who has trained herself to notice what rises unbidden when she is indeed still. Whether one calls that divination, intuition, or garden-variety good sense may depend less on metaphysics than on temperament.

Timekeeping, for Nakagawa, means something other than the tyranny of minutes. It means attending to cycles as they present themselves: one tree sketched in August and again in October; a California poppy bush that, even in a single glance, contains the whole arc—bud, bloom, ruin, seed. Regarding other methods used to track the natural world, she admires the meticulous phenology wheels that others produce, but her own loyalties lie with what she calls “spark journaling”: following whatever tugs at the eye that day. The method—if it can be called one—appears to trade discipline for whim. The effect is the opposite. When you stack a season’s worth of “sparks,” the pattern asserts itself.

Teaching, in her classes and community workshops, begins not with taxonomy but with breath. New people arrive certain that they “can’t draw.” Their hands tighten; their lungs, too. She assigns continuous line contours and deliberately wobbly observational sketches to sneak past the inner auditor. “If leaves can be beautifully imperfect, why can’t our drawings?” she asked. The question sounds like a kindness until she presses the point: perfection, as we worship it, is an industrial fantasy—rigidity and machined parts, not a forest. One student, who had lived in the same house for three decades, looked out her window after a session and drew the hedge she had walked past daily. She said she’d never really seen it until then.

Autumn makes her expansive. The Central Coast does not contain the myriad of fiery canopies in a New England Fall-scape—her East-Coast friends remind her of this—but if you’re willing to look, the color is there. Along Highway 1, she named two liquidambar trees “the Scarlet Sisters” for their annual turn to cranberry red against a silver trunk. The ritual of greeting them on errands, a private liturgy, had the practical effect of making the day better before it properly began. Fall also asks a quieter question: what can be set down so that rest has somewhere to land? In a culture that rewards only forward motion, this can sound like heresy. In a garden, it is ordinary.

When venturing out at night with journaling in mind, she uses a red headlamp to keep the dark intact. Constellations can be captured through observation; the first birds of the dawn chorus can be noted by sound. A neighbor’s barn-owl box, twenty feet from her house, once kept her awake with the scratchy insistence of owlets. She later drew her observations, compared their shapes to an age-chart she found, and knew, finally, from the sudden absence of noise, that they had fledged. “You get these small but perfect stories,” she said, with the satisfaction of someone who has learned to recognize enough.

If all this edges toward the spiritual, she is careful with terms. She does not audition as anyone’s guru. The point is not what a rose “means” in the abstract but what this rose, under this nose, in this morning’s light, suggests to a particular human. “I want to create space so people can sense what’s being said to them,” she said. Her job is less to interpret than to keep the room—literal or virtual—soft enough that people will risk paying attention.

Her calendar includes short courses, an online “Drawn into Nature” program, free sessions at the Carmel library, and the occasional retreat, local or overseas. The through-line is plain. Quiet the critic. Follow what sparks. Listen beyond the obvious. Write down what you notice, so that you can notice more the next time.

There is a temptation, in our age of gadgets that count what you could count yourself, to ask where the utility lies. What will a messy page produce? The answer may be embarrassingly small: a calmer walk to the grocery store, a more tolerant glance at a hedge, a private message that may or may not belong to frogs. But accumulation is its own phenomenon. A stack of such pages is an argument—not against science or schedules, but for another rhythm running alongside them.

A final defense of scratch paper. In school, the tidy answer went in the box; the rest was discarded. Nakagawa’s journal keeps the workings: the false starts, the surprising purple where two parts of a life bled together, the line that wanders and still finds what it meant to find. The conversation, in other words, not just the conclusion.

For more info on Melinda’s courses and events, please visit sparkinnature.com and follow @sparkinnature on Instagram