Each autumn, communities across Mexico, California, and all over the world, turn their attention to the dead. Día de los Muertos or Day of the Dead, is not a single ritual but a network of gestures: an arrangement of flowers, food set out for loved ones, smoke rising from resinous inscese, candles burning late into the night. To outsiders it can appear festive, even theatrical—symbolic images of skulls and face paint, processions, parades and music—but to those who practice, it is an act of continuity, a confirmation that the dead have not vanished so much as crossed into another room.

The holiday’s modern shape, observed on November 1 and 2, carries traces of both Indigenous cosmology and Catholic adaptation. Centuries ago, Aztec and Mexica peoples marked a season of remembrance for the ancestors, believing that the spirits resided in Mictlān, the underworld, and could return when the veil between worlds grew thin. After colonization, these traditions were folded into holidays observed by the Spanish Church such as All Saints’ and All Souls’ Days. What remains is a hybrid observance that persists precisely because it changes.

The people interviewed here—Carolina, Anagemma, Carlos, Nicole, Chezarae, and Mimi—each describe a different entry point into the same practice. Their experiences suggest that Día de los Muertos is less about mourning than about maintenance: of memory, of lineage, of a relationship with death that Western culture tends to suppress.

Carolina

Carolina grew up in Mexico— Celaya, Guanajuato and describes a childhood in which Día de los Muertos arrived through school as much as home. Each classroom would make an altar during the season; sometimes there were competitions; sometimes one altar would be selected and displayed downtown, among the official setups the city presented. At home, her mother kept pictures of the dead mixed in with the living, an everyday arrangement that made the dead part of the household, not a special-occasion appearance. The specifics vary by region, she says, but the intention remains: a time to honor death and the dead, to connect and commune.

As an adult, she keeps her ancestors out “all the time,” then reconfigures the altar by season. When the veil is thin—she names a period of months, not days—she makes offerings, often raw and simple foods: tomatoes, potatoes. She then sets out crystals, lights, and flowers. The practice is more solitary now; as a child there was a team. She also “hangs with them,” especially around All Saints and the Day of the Dead: a beer one of her grandparents liked, music, dancing—“a little party with them.” The altar, for her, is a portal, an energetic anchor for the spirits to meet the living; light shows them the path; food is there to enjoy.

There are regions in Mexico, she notes, where people go to the cemetery and literally keep company with the bones; she believes in Oaxaca some take the bones out, though she stresses that is specific, not general.

This year, she isn’t adding anyone new to her family altar, but she is creating a public one in San Jose at the Mexican Heritage Plaza. That altar honors the earth and all living beings—plants, animals, humans—and she calls it “in a way, political,” meant to remind us that all of those beings live under violence. She is making a map of the earth from traditional textiles of Indigenous cultures of each region, adding natural materials—rocks, leaves, grains, beans. The altars will be on display from early October into early November; there will be a large Día de Muertos event with music, vendors, food, art. She has worked the event as a tarot reader since 2020 but plans to attend this year simply to enjoy it. The symbols she always includes are consistent: cempasúchil (marigold), bones, sugar skulls, candles, and bowls of water.

Her view of popular culture is double. She feels the tradition is often watered down. At the same time, she sees adaptation—by people, even within capitalist systems that watch and absorb—as a kind of resistance, a way the tradition persists and stays alive. If pressed for one word for the spirit of the day, she chooses “remembrance”: of the dead, certainly, and of the living fact that we will die, which is also a reminder that we are, right now, alive.

Carolina is honoring Jose. Beloved friend, son, cousin, and fellow human. “Your kindness, care, curiosity, smartness, and sensitivity is deeply missed. You are loved.” -Carolina

Anagemma

Anagemma is from Salinas and says that she has been celebrating Día de los Muertos all her life. Her altar goes up on November 1st and stays through the month; a simpler, more intimate version remains year-round for “our close people.” On the day itself, there is dancing for the ancestors. At home they practice rituals like burning sage, but for the holiday they take it to the community: anyone can come, add a photo, and watch. It is, she says, “a community thing. Everybody is welcome.”

Her account is practical, tactile. Pictures and many flowers. Candles—“really lots of flowers, candles.” Sometimes sugar skulls. Warm foods to share—atole, champurrado —and Mexican bread. Atole, she clarifies, is “kind of like a hot chocolate,” with different flavors. The altar sits in the living room. This year, she says, it will scale up: more people have joined their Danza Azteca group, and they’re asking every participant to bring a picture of someone they’ve lost for a community altar.

Asked how the portrayal in popular culture lands with her, she says not enough people celebrate it; she experiences it as a Latino tradition that many others might embrace if they knew it better—if more people posted and talked about it—especially those with recent loss who could find solace in a day of remembrance. Her own understanding has matured. As a child, she says, she didn’t fully grasp it—some of the remembered had died before she knew them—but now it helps her and others tell and hear stories, to remember and cherish “every single person,” even those she never met. When asked for a specific memory, she offers the outline of one: her grandmother, Gemma, who died when she was about two and for whom she is named after. She has heard “a lot of wise things” about the woman who raised her mother, fought, endured, and is the one person she wishes she could meet now.

What she hopes outsiders learn is that the day is not only a holiday but a way to connect with others, a chance for those who’ve lost someone recently to grieve together; it can bring people closer. If she had to reduce the spirit of the day to a single image, she says, it would be loved ones looking down on us.

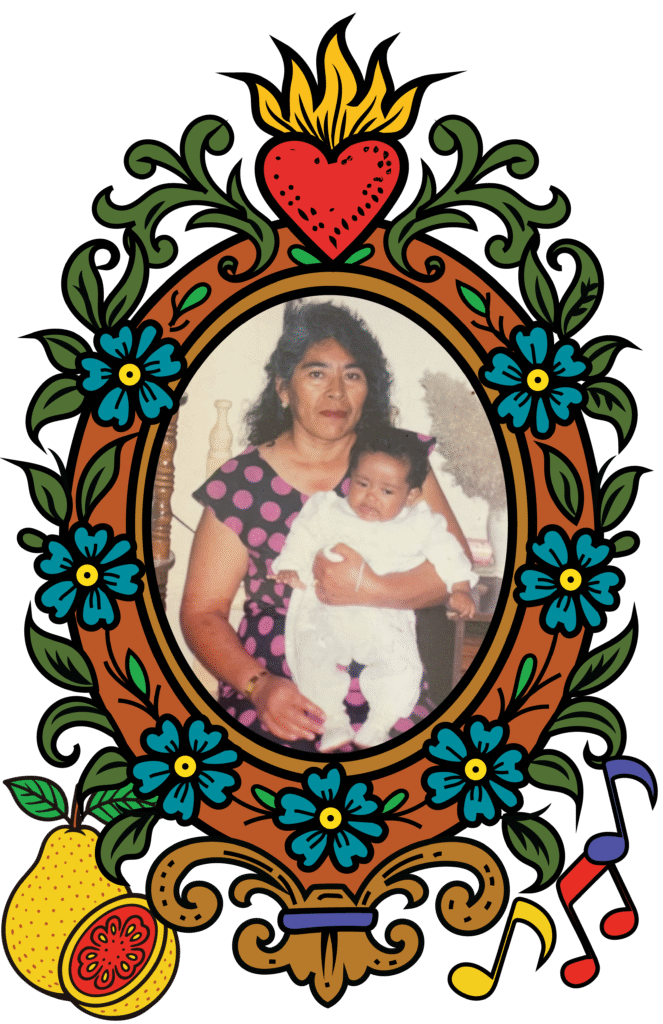

This year, Anagemma is honoring her grandmother, Gemma Rosas. She loved the fruit guayabas, music, and singing!

Carlos

He dates his practice to “maybe like 15 years ago.” The culture around Día de los Muertos wasn’t big in his family, he says; his father is from Jalisco, but didn’t really bring the holiday over when he came to the U.S. Now Carlos starts preparing on October 31st—buying small things earlier in the month, then setting up an altar (or ofrenda) on the 31st for November 1st and 2nd. The guiding principle is simple: put out what your loved ones liked when they were living. If your grandmother liked Marlboros and whiskey, those belong on the altar. Place it where the energy feels right—on a table at home or at a gravesite—so the people you love, and even older ancestors you never met, can “come through.” It is both commemoration and connection, an anchoring to “your culture in a long-term, ancestral sense.”

When he tries to name what the holiday means, he resists a clean answer: it’s “a hodgepodge of emotions,” a swing from celebration to introspection. There is the reality check—“you’re gonna die someday”—and with that comes ceremonies and sadness. He also calls it medicine: not in the Western sense, but “spiritual” medicine that lets you confront what hasn’t been dealt with. If you had a bad relationship with a grandmother who died, making her an altar and sitting with it can help “in a metaphysical” way, as he puts it. The public side of his year centers on an Aztec/Mexica community ceremony: Aztec dancers gather; people bring photos of their loved ones; the names are spoken aloud “to call them through the portal” so they can enjoy the dance and be part of the festivities. He keeps an altar up all year—“just random things on there”—and then, for the season, moves it aside and layers in traditional elements.

A few of those elements come with stories. Lore around the marigold flower is connected to a time before colonization. He mentions an Aztec story of two lovers transformed, one into a marigold and the other into a hummingbird, reunited around the flower. Tobacco, when burned, carries prayers upward in its smoke. Skulls belong because the underworld deities in old codices were depicted with skull faces; a single image could tell a whole story. He notes, too, the way the holiday changed under Catholic and Spanish influence—folded into All Saints’ dates, crosses added to altars, the three-tier structure associated with this world, purgatory, and heaven—and how public celebration in the U.S. was long suppressed, only re-emerging more openly in the mid-20th century. Today, he sees differences everywhere: some keep to older forms; some add face painting or references to the four directions and elements; intentions matter more to him than a single “right way,” though he draws a line at empty performance—painting faces, getting drunk, calling it culture.

The altar, he says, is the focal point—like a Thanksgiving table where everyone brings something. His own method is iterative. He starts by deciding whom to represent; it’s hard to include everyone, so he chooses, then tries to “connect with them,” an intuitive check on what would please them to see, smell, or taste. A theme emerges; then he gathers pieces—some already at home, some to be bought—and arranges and rearranges until the flow feels right. He mentions that his altar these days has four levels.

Asked to distill the spirit of the day, he lands on a sequence: reverence and a deep, quiet solemnity—not sadness, exactly, but going inward—followed by reconnection, and finally joy: “celebrating, dancing.” The procession is serious, he says; the celebration of life comes after. He points to large ceremonies at a plaza in San Jose, and a smaller one he participates in at Salinas, where, he says, “the altars there are like legit.”

Carlos is honoring his grandmother Lydia Aronce who loved reading the bible.

Nicole

Nicole is from San Jose, and came to Día de los Muertos relatively recently—within the last five years. She was raised Catholic and remains spiritually open now, a change she ties to personal events in that same span, including the deaths of relatives she was close to. This year, she says, will be “a lot more impactful” due to the death of her fiancé; she plans to do “extra special things” to honor him. In the beginning she joined other groups’ events, writing loved ones’ names on notecards for shared altars. Over time, the practice shifted homeward: a dedicated altar space in her house, a day spent visiting “a couple of his favorite spots,” flowers, and cooking one of his favorite meals.

Her description is particular and composed. She keeps photos, letters, pieces of clothing; “mostly photos,” she says. For her fiancé, food means sweets, enchiladas, even a hamburger, fast food, a Slurpee—“kind of random,” she admits, but faithful to who he was. She also plans a small photo shoot: the customary makeup and a flower, dressed with a picture of him. For maternal relatives, she reaches for religious items like rosary beads. The point, she says, is to connect to the “energy of the past loved ones,” to keep their personality alive, not just on the holiday but always, with the day set aside to honor and memorialize.

She keeps a small altar space up all year and adds to it as needed; when she runs out of room, she makes another spot nearby. One little area is now devoted to her fiancé—his ashes set in glass, items of his—“going to stay there forever.” The broader altar includes marigolds and favorite flowers (she mentions her grandmother’s love of daisies, and sunflowers and their variations).

She notes different ways people celebrate: once she visited her grandfather’s grave and saw how families gather at the cemetery; her own family doesn’t celebrate as a unit, so she does more of it alone. Because her fiancé was cremated, she’ll “have to make something” for him.

For those unfamiliar with the day, she pushes back against the idea that it’s about ghosts; it’s about energy and love, about keeping the spirit and personality of the dead alive and, for a day, “connecting with them as if they are still here.” It should be “a happy holiday,” she says, despite circumstances. Asked for a single image or feeling, she chooses “celebration”—and, earlier, a phrase more exact still: “confetti of flower petals,” a burst that points toward life.

Memory of Chris:

“I have so many great memories of Chris that I cherish, but one that I am particularly fond of is the memory of our first trip to Monterey together. We had recently reconnected with each other after 14 years apart and decided to take a spontaneous trip to the aquarium. He was in the process of recovering from a foot injury, but insistent about going because he hadn’t been there since he was young. We had the best time that day, despite his slight hobble. He looked like a little kid wandering around viewing all of the exhibits and was especially excited about the sea otters. We decided to make a tradition of taking a picture together in front of the orca whale near the bridge each time we returned. Afterward, we spent the rest of the day exploring Cannery Row, joking around and enjoying each other’s company. It felt like we were teenagers all over again. Neither of us wanted to leave until after the sunset. From that day on, we were nearly inseparable until the day he passed away.”

This year Nicole is honoring her fiancé Christopher.

Chris loved music (listened to rock & numetal most often)– favorite song: So Far Away by Staind.

He loved coffee, desserts, hats, sports (49ers,Giants,Warriors), animals (otters, dogs), Slurpees, Chilis, LOTR, and Star Wars

Chezarae

Chezarae is thirty-four years old, grew up in San Diego, and recently moved back to California from Rhode Island. He is half Mexican and grew up in the church, where Día de los Muertos wasn’t accepted. About five years ago, after he began following his own spiritual path—connecting with his higher self and spirit guides—he felt drawn to ancestral work, and through that, to the day itself. The practice takes two forms: a year-round presence of the ancestors on his altar, and then, on the day, a full dedication to them. He lays marigolds, sets out water and food offerings, lights candles, and always puts down a fresh cloth—something newly purchased, “clean and fresh”—that he’ll then use through the year. The only photo he has is of his grandfather, the ancestor he knew and has pictures of; he also calls the names of others he knows, even without images.

He speaks of the day as one of remembrance and offering—feeding the dead, letting them know they’re honored, reaffirming that “they’re still a part of us.” Ancestral work, he worries, can be forgotten; the holiday formalizes the call for support we have within our own line. It is also a reminder that the ancestors are always with us and that life is short; the ritual comforts the living while keeping attention on the dead. His relationship to death changed when his grandfather died: grief became more of a “happy remembrance,” a sense of connection with the dead in spirit form, and the fear of death receded. He tells a story his grandmother told him about the day he died—that shortly before his passing, he cried, reached out, and called for his mother—and says hearing it firsthand made him feel more at peace with what comes. This year he will honor his grandfather; he also feels newly pulled to honor his grandmother on his father’s side, whom he never met in life but who has appeared in readings he’s had.

In popular culture, he thinks the holiday has kept close to its true meaning; he cites the movie “Coco” as getting it right and says it hasn’t been over-saturated or “bastardized” in the U.S. He also believes the day resonates because honoring ancestors crosses traditions—he names practices that aren’t Mexican, as well as the way some Christian remembrance works, even if it isn’t named as ancestral work. The belief that ancestors visit is, to him, “universal.” As his own practice has deepened, he’s tried to understand the symbols—marigolds, candles, what they invite—and to take the day more seriously. Asked to condense its spirit, he answers without ornament: celebration.

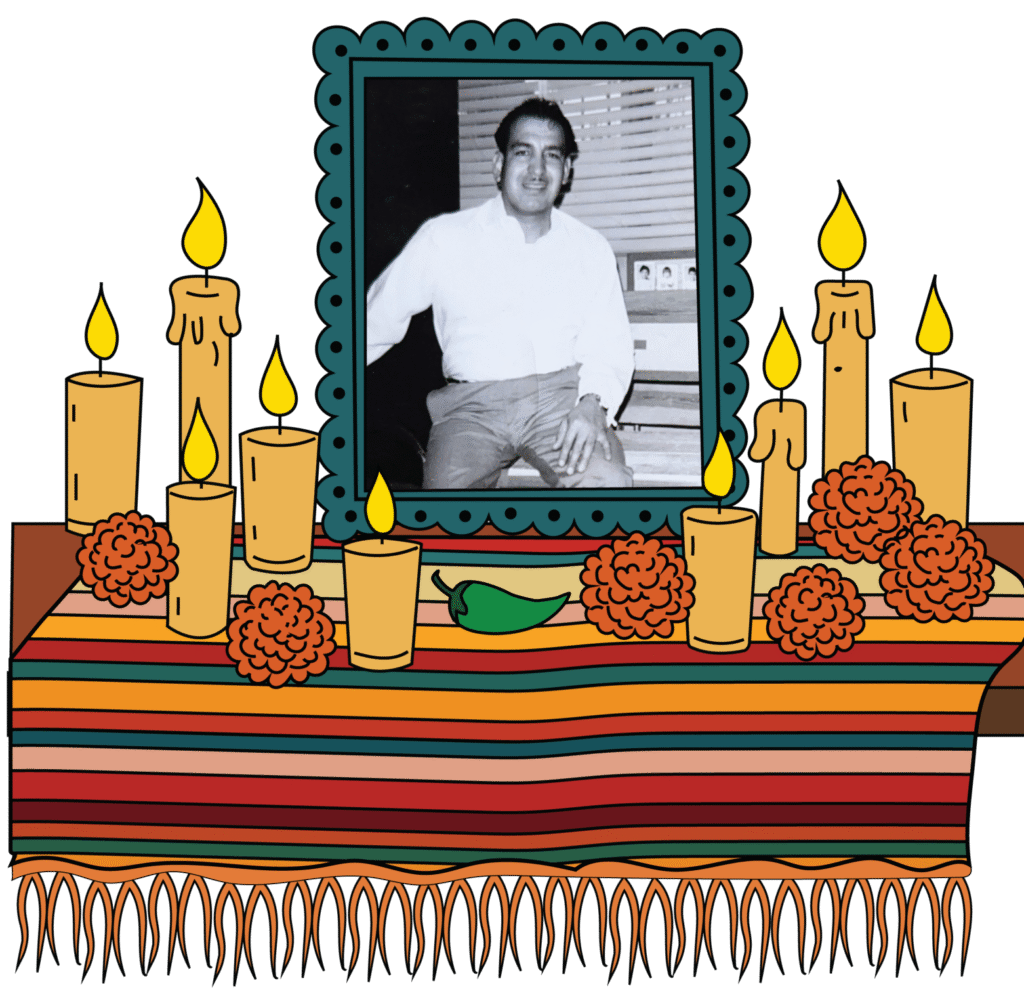

This year Chezarae is honoring his grandfather who would often walk around with a jalapeño in his pocket.

Mimi

Mimi is from Watsonville, born and raised; her family is from Jalisco, and she traces her first memories of celebrating to elementary school—seven, maybe. The way she does it now is both steady and seasonal. She always sets up an altar, and her preparation begins in September. “The earlier the better,” she says; in those weeks she holds her ancestors in mind, a process that feels like readying for a visit. On her altar go her grandparents—“all my grandparents have passed”—some friends who have died, and a photo of her last pet. She adds elements from nature: water to honor water, and for loved ones to drink; “earth” in the form of food, usually bread because it can sit as long as the altar is up. She places small favorites—tobacco for her grandfather, who smoked; canela because he liked cinnamon tea; matchboxes for her grandmother, the specific brand shipped up from Mexico—so that even routine gestures in her home become acts of remembrance.

She keeps a year-round altar too, a simple prayer space set facing east “where the sun rises,” with a mat of tule and a vessel—she names it as a bebetero popoškomí, an incense cup—where she burns copal and herbs. She uses what she has and what she’s gifted: sage, rosemary, lavender, cedar. For Día de los Muertos itself she adds candles—“traditional,” she says—and cempasúchil, the marigold. The meaning of the day for her is spiritual, bright, and cultural; it is a day she can speak freely about spirituality and the connection to ancestors and culture. She calls it a reset: preparing brings up sadness—her grandparents died in October—but also a balancing, a way to track where you are in the cycle of grieving. The holiday softens any opposition between life and death; she sees them as one.

This year she plans no new practice at home, but she notes a widening circle: her nonprofit held a community ceremony in Watsonville last year and will do so again, bigger this time. Ordinarily she celebrates quietly, at home; she and her parents have dinner, and she goes with them to Catholic church.

In popular culture, she sees non-traditional portrayals and some commercialization, and she dislikes the mixing with Halloween—“two separate holidays”—but she is glad the day has become part of more people’s lives, including Mexican American life. She thinks it is stronger when people keep and share traditions, giving the practice its “space.” She also describes regional differences: in her region of Mexico, people go to the graves—often the day before—bring coffee and bread, play songs, and it becomes, in her words, “a party.” Altars themselves can be flat on a table or stacked in tiers—two, three, up to seven. There is, she says, no right or wrong way: “It’s your altar.” As to why the day resonates beyond Mexico, she returns to the human fact that everyone grieves, and to the shift she’s seen toward “celebrations of life.” If she had to give the spirit of the day a single image, she chooses “light”—the sun, the warmth in candles and marigolds and food, even the tobacco she lays for her grandfather. Death is often imagined as cold, she says; memory brings warmth back.

Mimi shares a memory of her grandfather:

“When I was around 10 years old. It was on new years eve. We had balloons tied to a couple strings from tree to tree in the patio where we were celebrating. Our tradition is to pop all the balloons at midnight. So the clock stuck 12 and we all started popping the balloons. I could here my grandpa laughing. He’s a very serious man so I was surprised to hear him laugh. Turns out that while everybody else was struggling to pop the balloons, my Choncho (grandpa) had a cob with ember at the tip. He was using that tip to quickly pop the balloons. Looking back I now know that was his inner child in that moment. I miss him very much.”