Every era seems to produce a drink that’s more than a drink, an object of myth, a mirror for its age. For the fin de siècle (end of the 19th century), that was absinthe, my favorite spirit! This infamous green elixir was hisotrically beloved by poets and painters, feared by doctors and priests, and worshiped in cafés as if it were liquid sorcery. When the French called it la fée verte, the green fairy, they weren’t only naming its color; they were recognizing its spell.

Absinthe begins with a single herb, Artemisia absinthium, better known as wormwood. Bitter, silvery, and aromatic, wormwood has appeared for centuries in medicine, magic, and scripture. The Bible names it as the star that fell from heaven, turning waters bitter in the Book of Revelation; medieval witches burned it to summon spirits or guard against the evil eye. It is sacred to Artemis and Diana, goddesses of the moon and the wild, and paired with mugwort it was said to open the inner eye—the ingredient of dreamwork, clairvoyance, and astral travel. When distilled with anise and fennel and awakened by cold water poured over sugar, wormwood becomes something else entirely: absinthe, a shimmering portal between the sacred and profane.

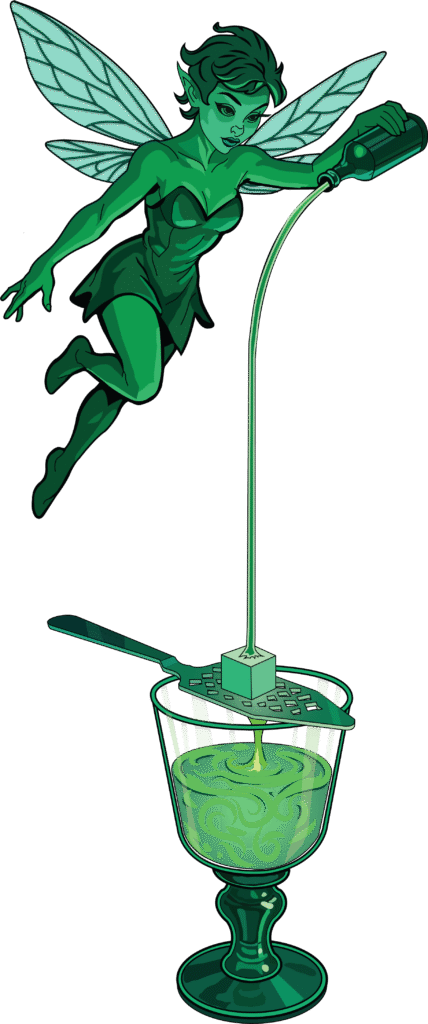

In the late nineteenth century, that ritual, which includes the slow drip of cold water, creating the swirling cloud of botanical essence, called the louche— was a kind of everyday alchemy. Painters like Toulouse-Lautrec and Van Gogh, poets like Baudelaire and Verlaine, saw in absinthe a green key to vision. They drank not just for intoxication but to alter perception, to catch the divine flicker behind ordinary light. Esotericists from Eliphas Lévi to Aleister Crowley described it as a spiritual catalyst. Crowley, in his 1918 essay Absinthe: The Green Goddess, compared the drink’s opalescence to a mystical rainbow—the same spectrum seen in alchemy’s “peacock stage,” the sign that transformation is near. To him, absinthe opened “the secret chamber of Beauty,” adjusting the mind to the frequency of art and revelation.

But every sacrament invites its heresy. By the early 1900s, doctors and moralists declared absinthe a poison and its drinkers degenerates. France blamed it for madness, infertility, even military weakness. Switzerland buried it with mock funerals. The United States banned it in 1912, years before national Prohibition. Behind the hysteria lay both moral panic and misunderstanding: thujone, the neurotoxin in wormwood, exists only in trace amounts, far below truly dangerous levels. What many called “absinthe madness” was more likely the result of strong drink, poverty, and suggestion. Yet myths cling hardest when they serve a spiritual hunger.

Absinthe’s mystique survived its exile. It became the emblem of the artist as visionary, half-saint, half-sinner—the one who drinks to see beyond the veil. Its ritual endures because it feels like ceremony: the sugar cube dissolving like an offering, the color changing from emerald to pale mist, the faint perfume of anise rising like incense. The experience is part chemistry, part meditation. You sit, you wait, you watch, and for a moment the world softens at its edges.

When absinthe returned to legality in the twenty-first century, it came back quieter, stripped of its scandal but not its symbolism. Wormwood remains a plant of paradox—both poison and protection, both gateway and guardrail. Modern witches still burn it on Samhain to call ancestors; bartenders still treat it as the spirit world’s aperitif. Its taste, at once medicinal and seductive, reminds us that beauty is often found in bitterness.

To drink absinthe well is to practice a small act of gnosis. It is to honor transformation—the shift from clear to clouded, from ordinary sight to second sight. The green fairy no longer promises madness or miracles; she whispers something simpler, older, and truer: that perception itself is the real magic, and that a little bitterness, properly transmuted, can turn to revelation.