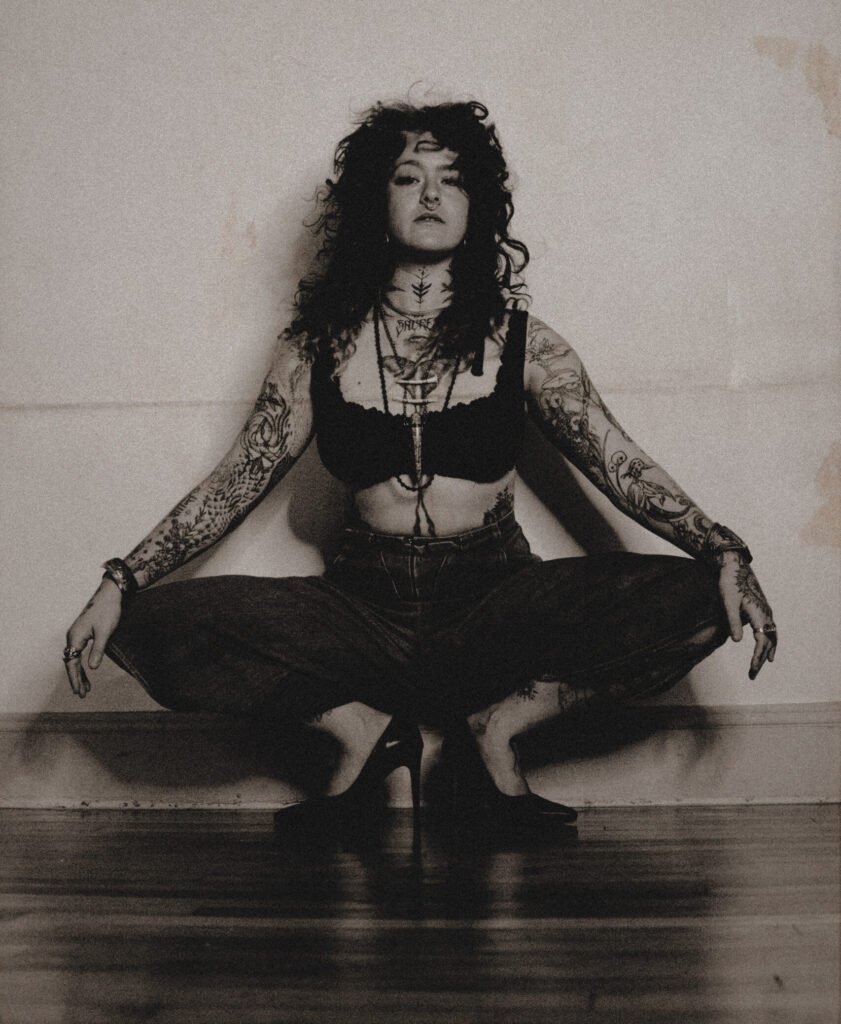

New York-based tattoo artist, Talya Alsberg was just thirteen when she first considered tattooing as a profession. Her mother is an artist, so walking the path of a creator and innovator was a given. She describes her upbringing as “international.” A way a being that has inspired a life without borders or too many pesky self-limiting beliefs. Talya’s decision to become a tattoo artist only raised a question of how, not if. She considered the apprenticeship route, but as it was presented then—masculine, hierarchical, unpaid, a kind of relearning of art in someone else’s image—didn’t suit her. She left it alone.

She kept drawing anyway. Illustration was a throughline, joined by sculpture and other art-forms like photography—moving from Seattle to New York for school. Near graduation she decided to teach herself to tattoo. Her life as a professional tattoo artist began four years ago. She simultaneously carried with her a second track that had been developing in parallel—an intensifying spiritual practice that, at the start, braided itself tightly into the work.

Those early sessions were overtly ritualized. Alsberg used a standard machine and standard inks—the logistics were conventional—but everything around the logistics was not. Appointments began with a guided meditation that could run an hour, followed by thirty minutes to an hour of conversation to translate what she calls “what was happening in the ether” into the room: embodiment, narrative, meaning. She sat in her own practice, too, before meeting a client; the session functioned as ceremony.

It was powerful and, she realized, difficult to sustain. “With that level of deep meditation you reach really, really far away spaces,” she says. Some clients could hold that space with her; many couldn’t. The process simplified. Less ascent, more ground. Alsberg shifted her attention to “the nervous system,” to the baseline of the body, the lower chakras—“very, very physical and much less about traveling upwards.” The tactile work, she noticed, takes people upward on its own. Her preparation changed with it. She doesn’t sit now to meditate before each appointment. Much of the connection work happens at night, at home. The studio day is simple, human, present.

“Today I take care of my body more deeply,” she says. The preparation is life-scale: sleeping, eating, steadying, so she can meet someone and really listen.

What people want, when they arrive, often comes out obliquely. Some don’t know why they’re there; some are wary of not knowing. Many want to be seen. Many, very practically, want to solve a problem—find a job, move through a change, make sense of grief. The visible request—an image in a particular place—sits on the water’s surface; Alsberg’s task is to bridge that surface to the root. The tattoo, as object, is only part of it. The session is slow and close. “It’s about bringing what you want to be into the present moment,” she says, “into the most concrete thing that can be,” which is a permanent mark.

Asked for a name for her style, she resists. “Naming something can scare it away,” she says. People often call the work whimsical; she does a lot of botanical forms. In the language of Instagram, her drawings get tagged “trippy” or “visionary,” labels she accepts as search terms more than truths. The images themselves are less fixed than arrived at. Clients frequently come in with something of hers they’ve seen and want to echo, but the conversation redirects. A recent appointment began with a request for floral work and ended with “sparkly sewing scissors”—a piece that emerged as the client talked about ancestry and the cutting of patterns. There are patterns in that larger sense, Alsberg says—people on self-trust journeys, people learning to honor their choices, their dreams—but the visuals meet the individual in real time.

Placement matters because scale and position are their own kind of speech. A small image tucked along the inner rib differs, in what it comforts or declares, from something that spreads across the chest. Some clients are laser-specific about location for exactly that reason. Others want to follow what unfolds in the chair. Alsberg accommodates either mode. She keeps her approach spare—“very simple”—to leave room for connections to show themselves afterwards. Her real debrief happens when she’s home, lying down, unwinding from the energy of the day, noticing how the threads from the session braid together in hindsight.

The hinge on which many sessions turn is timing. People find her, she says, at pivotal points—grief, moves, new jobs, endings and starts of relationships. She has watched partners mark a bond and, sometimes, witness its end in the same arc of time. The transformations are large enough that clients sometimes feel an “unknown anxiety” about coming in; they sense a precipice without language for it. Alsberg understands the sensation. Her job is to keep the ground steady enough that the step can be taken.

With that comes responsibility—practical, ethical, energetic. Alsberg mostly works with women and non-binary clients; she sees few men. Many of the people who find her are young, nineteen or twenty—and she remembers her own headlong certainty at that age. She doesn’t regret her tattoos, she says, but she does wish some choices had been given more time. She encourages clear speech for maximum clarity but also welcomes uncertainty as part of the process. Sometimes a client discovers that freehand drawing isn’t for them. Sometimes they change the plan entirely, shrinking an idea or letting it bloom “from here to something enormous.” Because she books one person a day, there’s room for the change itself to become the ritual.

As for other people’s ink, she stays out of it unless invited. If someone asks her to revive an old piece, to cover or add, then the earlier work enters her field. Otherwise, she keeps her attention “very, very present,” looking forward just far enough to set someone up for what they need, without naming another artist’s intent.

The evolution of the practice has been, in her telling, a practice with time. The longer she works, the more the medium rewards patience. Each tattoo teaches—about skin, about needles and their behavior, about people, about the “hearty things.” The lessons don’t arrive in order; tattooing, which must be made in order—line by line—has a way of bringing that scattered knowledge to earth. She once imagined a studio where others might practice in this way. It may still come. For now, she is focused on slowing down. “Everyday just slow slow slow slow,” she says, laughing at her own repetition. “I’m super grounded right now.”

If she had to define her work in one sentence, she offers three words: “rooted in love.”

Outside the chair she is drawing—working on a series of illustrations. Her prints are available online.

For more information, please visit TalyaAlsberg.com and follow her on Instagram @_TaDoula_